INFECTIOUS AGENTS

C.diphtheriae is a non-motile, non-encapsulated, non-sporulating gram-positive rod-shaped bacterium with a high Guanine-cytosine content (Konig, C et al, 2014). C. diphtheriae is genetically heterogeneous and has four biovars which are defined as Gravis, Mitis, Belfanti and Intermedius (Thompson et al, 1983).

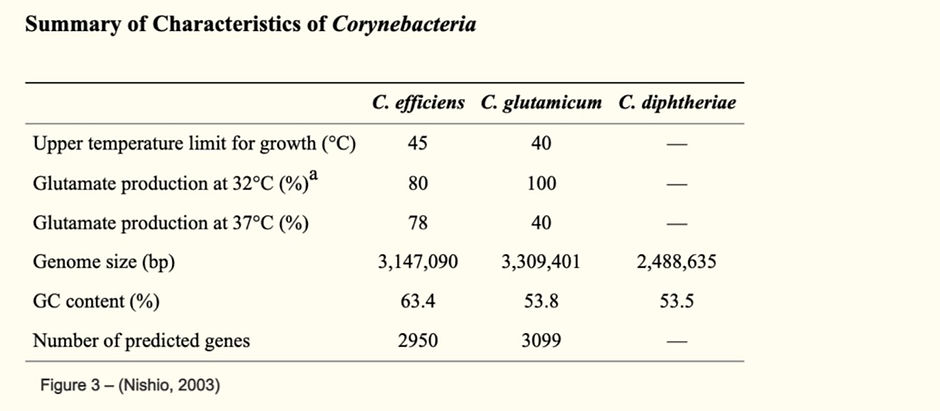

As shown below in table 1, C. diphtheriae had a GC content of 53% and a genome size of 2,488,635. In addition, this table shows that C. effeiciens and C. glutamicum have higher GC content, a larger genome size in comparison to C. diphtheriae and they also produce glutamate. C. diphtheriae does not produce glutamate due to the fact that it does not come from glutamic acid-producing species.

However, in the C. diphtheriae genome, the high Guanine-cytosine content is not constant throughout the whole genome as there have been findings that show that in the region around the terminus there is a significantly low high Guanine-cytosine content, and this reflects on its genetic diversity (Cerdeno-Tarraga, 2003). This is the cause of the 102 strains of C. diphtheriae and change in genome (Titov et al , 2003).

C. Diphtheriae toxins have 3 structural domains and each of them have a different biological function implicated in the intoxication of cells. The functions vary from cell surface binding, internalisation into endosomes and then crossing the endosome membrane to go into the cytosol and blocking cellular protein synthesis (Gillet et al, 2015). Moreover , C.diphtheriae toxins have a crystal structure which consists of 1,046 amino acid residues , including 2 bound adenylyl 3′‐5′ uridine 3′ monophosphate molecules and 396 water molecules (Bennett and Eisenberg, 1994).

In the cell wall of C. diphtheriae, it contains an arabinogalactan polymer that anchors an outer lipid‐rich domain to the murein sacculus of the cell. Alpha-alkyl, beta-hydroxy fatty acids and corynomycolic acids are produced through a Claisen-like condensation reaction between two fatty acyl chains. Moreover, there are pilli found on the exterior and sortase-like proteins are produced to help with anchoring of the pilli and polymerising them (Cerdeno-Tarraga, 2003) . As shown in figure 1, SpaA-type pilus is composed of a major pilin subunit SpaA and this is important for the formation of the pilus structure. pilin motif and the sorting signal are both necessary and sufficient to promote pilus polymerization by a process requiring the function of a pilus-specific sortase (Mandlik et al , 2010).

As shown in figure 1, DIP0733 is a transmembrane protein. DIP0733 is a multi-functional virulence factor of C. Diphtheriae. It has also been found that DIP0733 may play a role in avoiding recognition of C. Diphtheriae by the immune system and this protein is involved in adhesion, invasion of epithelial cells and induction of apoptosis. Moreover, DIP0733 has a c-terminal coiled coil domain which is essential when it bind to type I collagen, fibronectin and human plasma fibrinogen. Another protein known as DIP2093 is a SDR protein and is also involved in binding to Type I collagen and host colonisation (Antunes et al, 2015).

Moreover, CdiLAM is an adhesin of C. Diphtheriae in the first step of infection to human respiratory epithelial cells. The key structural features of CdiLAM are the linear α-1-6-mannan with side chains containing 2-linked α-D-Manp and 4-linked α-D-Arafresidues (Moreira et al , 2008).

References

Antunes, Camila Azevedo, et al. “Characterization of DIP0733, a Multi-Functional Virulence Factor of Corynebacterium Diphtheriae.” Microbiology, vol. 161, no. 3, 1 Mar. 2015, pp. 639–647, 10.1099/mic.0.000020. Accessed 3 Dec. 2020.

Bennett, M.J. and Eisenberg, D. (1994). Refined structure of monomelic diphtheria toxin at 2.3 Å resolution. Protein Science, 3(9), pp.1464–1475. [01/11/2020]

Cerdeno-Tarraga, A.M. (2003). The complete genome sequence and analysis of Corynebacterium diphtheriae NCTC13129. Nucleic Acids Research, 31(22), pp.6516–6523. [27/10/2020]

Mandlik, Anjali, et al. “Corynebacterium Diphtheriae Employs Specific Minor Pilins to Target Human Pharyngeal Epithelial Cells.” Molecular Microbiology, vol. 64, no. 1, 7 Dec. 2020, pp. 111–124, 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05630.x.

Nishio, Y. “Comparative Complete Genome Sequence Analysis of the Amino Acid Replacements Responsible for the Thermostability of Corynebacterium Efficiens.” Genome Research, vol. 13, no. 7, 1 July 2003, pp. 1572–1579, 10.1101/gr.1285603. Accessed 5 Dec. 2020.

Ott, Lisa. “Adhesion Properties of Toxigenic Corynebacteria.” AIMS Microbiology, vol. 4, no. 1, 2018, pp. 85–103, 10.3934/microbiol.2018.1.85. Accessed 5 Dec. 2020.

Titov, Leonid, et al. “Genotypic and Phenotypic Characteristics of Corynebacterium Diphtheriae Strains Isolated from Patients in Belarus during an Epidemic Period.” Journal of Clinical Microbiology, vol. 41, no. 3, 1 Mar. 2003, pp. 1285–1288, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC150260/, 10.1128/JCM.41.3.1285-1288.2003. Accessed 5 Dec. 2020.